In my last article on squatting, Squat Talk: Foot Position

and Ankle Range of Motion, I briefly brought up hip and knee strategies during squat

performance. The strategy used varies from person to person based on comfort,

how you learned how to squat, and anatomy (e.g. lever arms, how your hips are

positioned, etc.). A narrow stance squat will require a more knee-dominant

strategy and a wider stance squat will require a more hip-dominant strategy.

First let’s talk about some considerations when using a

knee-dominant strategy. Your feet will be closer together (narrow stance), the

knees will track further over the feet, and quads can carry more of the load

when compared to a wider stance. This strategy is seen in Olympic weight

lifting, because it puts lifter in a better position to get under the bar (aka

“the catch”) and finish the lift. Try that with a wider stance. It’s damn near

impossible. It is easier to get your ass to the ground with a narrow stance and

knee-dominant strategy if your ankle dorsiflexion range of motion is there.

Figure 1: As

the knee tracks over the foot and the distance between the knee and ankle gets

greater during the squat, the compressive force into the joint will increase.

With the wider stance squat, your feet are positioned

further apart. The knees will track over the feet slightly, but not a lot, and

more of the load will be carried in the posterior chain (aka your glutes and

hamstrings). This stance is seen more in powerlifting, when the competitors are

trying to shorten the range of motion and get a larger base while lifting maximal

loads. With this variation of squatting, getting to depth is the main concern. “Getting

to depth” refers to when the crease of the hip breaks the plane of the top of

the patella.

But what should your

hips and knees actually be doing?

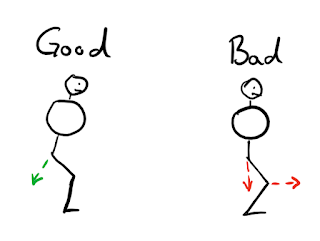

Figure 2: The

knees should stay over the feet, not track excessively forward, and not collapse

inward. Collapsing inward will put excessive force on the medial/inside of the

knee. Excessive forward tracking of the knee will cause high compressive forces

on the joint and will cause the heel to want to lift off.

Figure 3: The

hips move down and back during the squat.

These are some more things to take into consideration when

squatting. If your knees consistently cave in, I have found strengthening the

hip external rotators to be helpful, as well as verbal cues during the movement

as reminders. To learn how to move the hips down and back, like I mentioned

earlier, practicing squatting back to a box or chair to get comfortable with

the motion is helpful. This will also help with the translation of the knee moving

forward if this is a problem area.

Ryan Goodell, CSCS

P.S. – I hope you enjoyed and learned a little bit from this

edition of squat talk. If you are interested in other content that I am

producing on Weights and Stuff you can find them at:

YouTube: search Weights and Stuff (please like, subscribe,

and comment!)

Instagram: @weights_andstuff

Twitter: @weightsnstuff

Website: www.weightsandstuff.com

No comments:

Post a Comment